Fred Harvey

Visionary entrepreneur who paved the way for civilized travel when the West was still wild

Welcome to The Four Corners of the Southwest. My love for travel and the outdoors has inspired me to learn, research, and share interesting information about the American Southwest.

The Grand Canyon is one of the world’s natural wonders however, by the mid-19th century, the Grand Canyon remained a mysterious void, commonly called “The Great Unknown.” After the Civil War, America was concerned with Reconstruction and Westward Expansion.

When I was nine years old, my family took a trip to the Grand Canyon. I was enchanted by the Canyon and the nature surrounding it. In addition, being inside the Bright Angel Lodge was an experience in itself. It wasn’t just the beauty of the canyon, but it was the way I felt in the lodge. It was as if the person building it captured the essence of the Canyon within the walls.

I remember my parents talking about “Fred Harvey” as if he were going to pop out while we were having dinner at the Bright Angel Lodge. In the early 1970s the Fred Harvey Company still operated the concessions at the Grand Canyon. I didn’t realize until just recently how much of an effect he did have on tourism at the Canyon and throughout the Southwest. Fred Harvey civilized Westward Expansion. The Southwest and tourism wouldn’t be what it is today without his influence and legacy.

Who was Fred Harvey?

Fred Harvey (1835-1901) was a businessman and entrepreneur who immigrated from England when he was 17 years old. He recognized a need for better restaurants and overnight accommodations along rail lines throughout the Southwest.

Fred Harvey and his employees successfully brought new higher standards of both civility and dining to a region widely regarded in the era as "the Wild West." He created a legacy which was continued by his sons and remained in the family until the death of a grandson in 1965.

How Did He Begin His Business?

When traveling by train for work in Missouri and Kansas during the 1860s, Harvey experienced how bad train food was and approached the Atchison, Topeka, & Santa Fe Railway (AT&SF) in the early 1870s with the idea of providing passengers with attractive surroundings, superior service and good food.

The railroad company knew that this was one of the most serious problems of all the railroads at the time, so they enthusiastically accepted his proposal. Harvey negotiated with the railroad company that they would build and supply all the buildings free of charge and provide free rail transportation for foodstuffs and employees. In 1876 the Fred Harvey Company was founded, and the first Harvey House was opened for business in Topeka, Kansas in the spring of that year.

Why Was Railroad Food So Bad?

Before the days of railroad dining cars, passengers’ only option for food service along the way was to visit one of the local hash houses wherever the train happened to stop (usually at locations near the water stops – a place where steam engines stopped to replenish water). The food was terrible, and the service was even worse. The water stops were generally 30 minutes so passengers would rush in, place an order and just about the time the food arrived, the conductor called out “All Aboard.” Some restaurateurs bribed engineers to blow the all-aboard whistle ahead of schedule prompting diners to scurry out and leave large heaps of leftovers which the cooks would reheat and serve to the next shift of diners hours later. Yuck. Recycled food.

Providing Meals

Fred Harvey built dining rooms along the train route that guaranteed service within half an hour and is credited with creating the first restaurant chain in the United States. Food orders were telegraphed ahead so meals were ready when the train pulled in. The number of dishes available to customers was streamlined to aid in the quick preparation of meals.

Harvey insisted on high quality meals and that his chefs be professionally trained. French chefs were hired away from prominent restaurants in the East and paid handsome salaries. In at least one instance the Harvey House chef was making more money than the president of the local bank.

Part of the success of Harvey’s enterprise was the fact that the railroad provided and paid for transportation of foodstuffs. This meant that the raw materials for the meals was the highest quality and the freshest.

Harvey’s eating houses had formal, sit-down dining rooms (in which even cowboys were expected to wear jackets), attached to large casual dining areas with long curved counters (the classic American diner), attached to take-out coffee and sandwich stands (like McDonalds or Starbucks).

Revolutionizing America’s Workforce

In the 1800s only men were hired to wait tables. Fred Harvey decided to make a change in 1883 when a drunken brawl broke out among waitstaff in one of his New Mexico establishments. He fired the lot and hired women by advertising in newspapers on the East Coast and Midwest for “young women, 18-30 years of age, of good character, attractive and intelligent”. Harvey Girls became famous, and Judy Garland even starred in a movie of the same name in 1946. There’s a whole lot more to this story and will be the subject of my next post!

Dining Cars

Until the mid-1890s, few dining cars operated in the Western states and territories. As time went on, locomotives and tenders became larger and more efficient, therefore water stops became less frequent. To reduce train travel time, dining cars were developed to serve meals without stopping the train. In 1888–89 Harvey began operating a dining car between Chicago and Kansas City. In March 1889 a dining-car meal cost 75 cents.

Railroads lost money on serving meals in dining cars due to the cost of building a kitchen inside a rail car, cost of labor and the fact that the diner has no local business to help cover overhead costs. Harvey and the Santa Fe chose to lose a bit more money than the competing railroads at the time to provide the best dining experience. They made up for the loss by increasing ticket prices and good will providing good meals would bring.

Harvey Girls were not employed on the rails. All of the stewards were male.

Harvey Was a Pioneer of “Cultural Tourism”

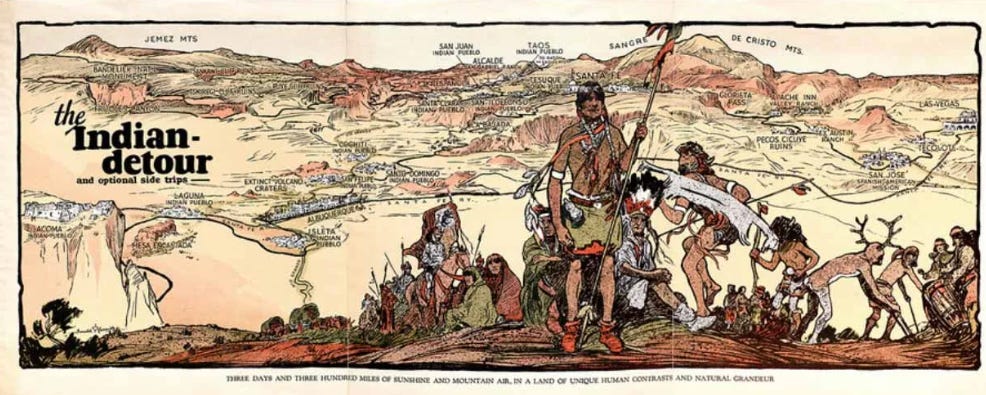

Fred Harvey was a pioneer of “cultural tourism” in the American Southwest in the late 19th Century and promoted the region by inspiring the “Indian Curio” show as well as guided tours called “Indian Detours”.

In the early 1900s, Fred Harvey's son Ford helped create an “Indian Department” which commissioned artists and photographers to capture the exoticism of “Indians” in the Southwest. These images were printed on everything from menus to brochures to promote the mystique of Indian Country and Harvey’s tourist enterprises.

The company also employed Native Americans to demonstrate rug weaving, pottery, jewelry making and other crafts at his Southwest hotels. The sales of those items significantly increased the revenues of indigenous artists and helped bring public awareness of a culture that had been virtually ignored up to that time.

Resort Hotels and the Grand Canyon

In 1903, the Santa Fe focused on the promoting tourism to the Grand Canyon. The Grand Canyon was virtually unknown until the Santa Fe began to publicize it. A branch of the railroad to the Canyon opened in 1901. The railroad built the famous El Tovar at the rim of the canyon as a resort hotel in which Harvey’s company ran.

The Fred Harvey Company hired Mary Colter as the resident architect for the company and she set out to design many of the historic buildings we can still visit today at the Grand Canyon such as Hermit’s Rest and the Watchtower. I’m working on a future post about Colter and her legacy.

The Grand Canyon complex of buildings was only one in a series of Santa Fe resort locations. So many of these locations have been torn down. The La Fonda on the Plaza in Santa Fe has been in continuous operation however and has some great stories which include Robert Oppenheimer, the father of the Atomic Bomb (subject of yet another future post). Other sites have been purchased and restored like the La Posada Hotel in Winslow, Arizona.

Legacy

At their peak, there were 84 Harvey Houses, all of which catered to wealthy and middle-class visitors alike and Harvey became known as "the Civilizer of the West."

Most Harvey Houses closed during the 1930s, 40s, and 50s as railroad travel became less prominent. The places that are still open are mainly either operating as hotels, such as La Fonda in Santa Fe, NM, or are part of the Grand Canyon Lodges, such as El Tovar and Bright Angel Lodge or La Posada in Winslow, AZ.

His story and his methods are still studied in graduate schools of hotel, restaurant, and personnel management, advertising, and marketing. He is especially popular in the fields of “branding” because “Fred Harvey” was actually the first widely known and respected brand name in America, established years before Coca- Cola.

The original Fred Harvey Company and its close affiliation with the AT&SF lasted until 1968 when it was purchased by the Amfac Corporation which was renamed Xantera Parks & Resorts in 2002. In 2006, Xantera purchased the Grand Canyon Railway and its properties. Xantera continues to the be official concessionaire of properties at the South Rim of the Grand Canyon.

Next Time

There’s so much to the story of Fred Harvey and his company. I’m working on (at least!) five other related posts. My next post will be about the Harvey Girls. The Harvey Girls were a signature component of Harvey’s success and one of his most enduring legacies. Check out my next post to learn about these “Other Pioneers” of the American West.

The photo of you from 1971 is priceless! Thank you for the history of Fred Harvey!

Fascinating! Remarkable story, reported so well. I’ve not really experienced Fred at the canyon but have been to La Fonda. So my list of to do is to check out more closely the Fred experience when I go to the Parks. I look forward to the new posts coming, right up my alley.